Ginkaku-ji

銀閣寺

Temple of the Silver Pavilion

Official Name:

Jishō-ji

慈照寺

Temple of Shining Mercy

- Website: https://www.shokoku-ji.jp/en/ginkakuji/

- Address: 2 Ginkakujicho, Sakyo Ward, Kyoto, 606-8402, Japan

- Nearest Stations: Mototanaka Station (28 min by foot)

- Nearest Bus Stop: Ginkakuji-michi Stop

- Bus Routes: 4, 17, 100, 203, 204

- Entrance Fee: ¥500

- Hours: 8:30 – 17:00 (Spring, Summer, Fall), 9:00 – 16:30 (Winter)

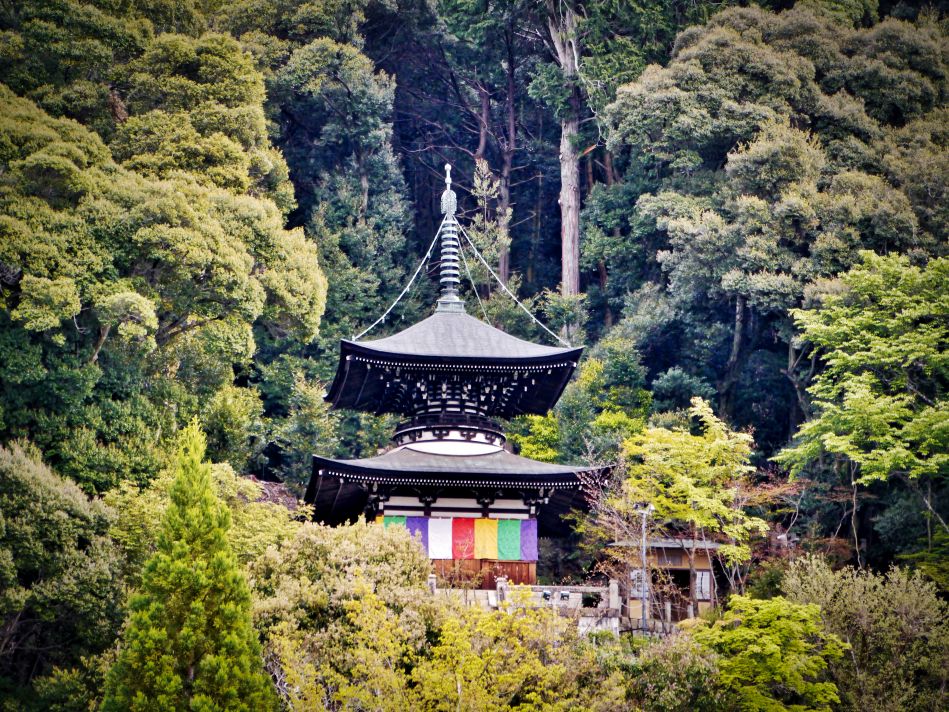

While not actually covered in silver leaf, Ginkaku-ji embodies grace in the form of a temple set in a wondrously lush landscape at the foot of Kyoto’s eastern mountains. No matter where you decide to stop and take in the view, you cannot help but let the delicate details and serene beauty sink deeply into your heart.

Ginkaku-ji History

Beneath the Ginkaku-ji’s ornate buildings, mossy under-growths, and handsomely lush trees, is a history spanning a thousand years. Long before the Ashikaga shogunate, the area around Ginkaku-ji was and is considered “as possessing a feminine gentleness” with numerous poems citing its natural and ancient beauties. Seeing this innate splendor, Buddhists in the 800s built a temple complex, but it fell into disuse after roughly 70 years. By the 11th century, it caught the eye of a grandson of an emperor, who rebuilt the temple and used it as a residence to live out his life as an abbot. This started off a trend in the Kyoto area to install royal descendants (both imperials and shogunates) as the head of heads of temples for the centuries that followed, including Jishō temple.

The Jishō-ji that we see today is a 1600s recreation of the 1480s version built by Yoshimasa, the prior version was destroyed in a fire during the Onin civil war. Back then, it was officially named Higashiyama-den and was built as Yoshimasa’s golden-year artistic retreat. It took roughly a decade to fully build the Jishō-ji complex, and Yoshimasa died before he could see its completion in 1490. Following his death, the Higashiyama villa was converted into the Zen temple and officially named Jishō-ji.

In 1550, a battle between the fifteenth Ashikaga shogun and an ambitious daimyo destroyed nearly all of Jisho-ji’s buildings in a fire — only the Silver Pavilion and Togudo survived. In 1615, the beginning of the Edo period saw the large-scale restoration of the temple which created much of the present Ginkaku-ji.

Finally, in 2008, Ginkaku-ji underwent major restorations. Modern preservation techniques were used to ensure what remains of the 1615 structures are enshrined for generations to come.

How to Visit Ginkaku-ji

Stay at a local Ryokan – Ginkaku-ji sits on the southern half of Sakyo Ward, neighboring Higashiyama Ward is home to several beautiful traditional Japanese inns. Do not pass up the opportunity to have the full cultural experience that Kyoto has to offer. If you stay for at least a night or two, you have will access to several temples and gardens. You will also save a few yens in transportation costs.

If you Must, Take the Bus – You can get to Ginkaku-ji by direct bus numbers 100, 17, and 4 from Kyoto Station in about 35-40 minutes and for 230-yen one way. You can also take the Karasuma Line (green line) north to Imadegawa Station, then take bus numbers 203 or 204 for 490-yen one way.

Go early, Go Mid-week – Due to Ginkaku-ji’s popularity, I suggest visiting early on a weekday. The temple grounds open at 8:30 AM during spring through fall, and at 9:00 AM in winter.

Stunning Autumn Colors – Some of the best autumn leaf spots in Kyoto are found around Ginkakuji Temple and Nanzenji Temple. One could spend 3 to 4 hours or more leaf-peeping.

Go Beyond – Ginkaku-ji is one of a few stops to see in the area. I suggest visiting other temples and gardens nearby.

Popular Spring – Everyone including locals loves Higashiyama’s temple area in spring. Bright greens and fluffy pink cherry blossoms are truly idyllic but be prepared for tourist crowds

Highlights of Ginkaku-ji

Kannonden Ginkaku – 観音殿 銀閣 – “Silver Pavilion”

The symbol of Jisho-ji. Though not really covered in silver-leaf, the Silver Pavilion is the central focus of this temple complex. Truly a photogenic building when framed by lush greens and the reflective pond.

Ginsyadan – 銀沙灘 – “Silver Beach”

In front of the abbot’s chamber are waves of white sand. Traditional Japanese Zen gardens use selectively combed rocks with sand to represent islands and seas. Ginkaku-ji’s Ginsyadan uses only sand, forsaking rocks completely. Why? Legends say that it was built to mimic the reflection of moonlight being held atop by Higashiyama.

Path to the Upper Garden

Just past the southeastern end of Nishiki Kagami Ike pond, and beyond the waterfall, is a path that leads up to the back garden. Here you will find mossy panoramas shaded by delicate trees. The path also leads to one of the best photography spots overlooking Ginkaku-ji.

Kinkyo-chi – 錦鏡池 – “Brocade Mirror Pond”

The tiny waterfall near the north end sends ripples along the pond’s surface, supposedly to “wash away the moonlight” when gazing on a clear night. During the day, the pond reflects the dark Silver Pavilion and the surrounding trees. At the south end of the pond, is a particularly lovely spot to view the Silver Pavilion nestled among the greenery. I am particularly fond of the view in the fall when the maple leaves turn bright red.

Get Out There and See More

Honestly, it does not take that long to view Ginkaku-ji and her gardens. If you walk at a fast pace, you could see all of it within 30 minutes. Therefore, I suggest that this temple be one of many stops of you tour in the area. For more details on what to see, read my Philosopher’s Walk article.